Data science against gender-based violence

Introduction

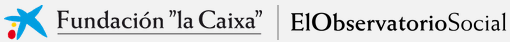

Gender-based violence is the violence suffered by women for the sole reason of being so and is the most serious manifestation of patriarchal culture, taking women’s lives or impeding the full development of their rights, equal opportunities, and freedoms. In Spain, in the period 2010-2021, 653 women have lost their lives due to gender-based violence, and 7 in 2022 (until March 14th). According to the Statistical Dossier of Gender-Based Violence 2020 published by the Catalan Women’s Institute, more than 16,000 complaints were lodged in Catalonia in 2019, 82% of which occurred in the scope of a sentimental partnership. Figure 1 depicts the number of gender-based violence reported cases in the different geographic areas of a particular health region in Catalonia, and it can be seen that the Covid- 19 pandemic has increased the number of reported cases dramatically, especially due to a differential behavior during the pandemic (mobility restrictions, mandatory confinements), and a training intervention conducted over health professionals in this area starting in mid 2018. Despite the large number of complaints, it is suspected that they represent only a small portion of the cases occurring, as for very different reasons, the victims often decide not to report the assaults they suffer.

Figure 1. Reported monthly cases of gender-based violence in each area of the North Metropolitan Region in Catalonia (Spain).

Figure 1. Reported monthly cases of gender-based violence in each area of the North Metropolitan Region in Catalonia (Spain).

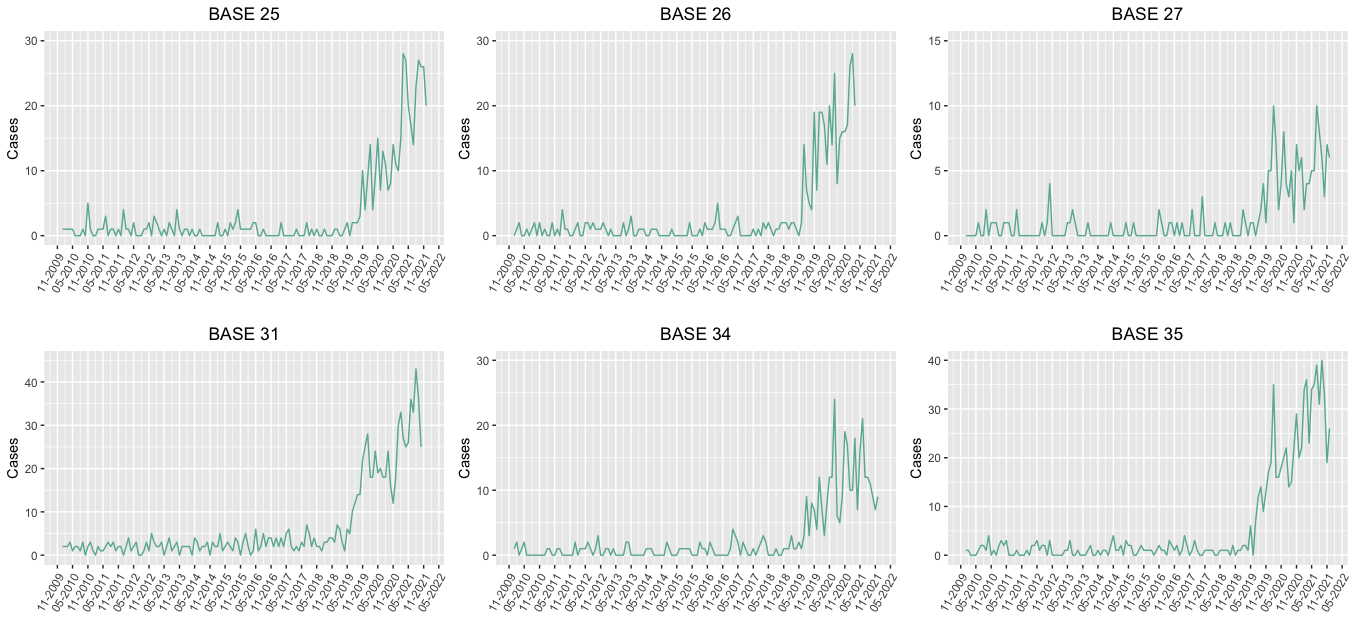

As reported in the document on tackling sexual violence in Catalonia, being a victim of sexual violence is often fraught with guilt that can lead to denial of sexual violence. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that the number of diagnoses related to gender-based violence recorded in the public health system databases may be underestimating the magnitude of the problem. It is clear that once an estimate of the real extent of the problem has been obtained, it would be very useful not to leave the decision to alert about a possible case of gender-based violence (especially for suspicious unconfirmed cases) to health professionals but providing them with a tool that can do it automatically, based on artificial intelligence methods and capable of identifying the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics that modify the likelihood that a woman might be a victim of gender-based violence. In 2019, the Ministry of Equity of the Spanish Government conducted a large survey on over 9,500 women over 16 years old focused on studying the prevalence of gender-based violence in Spain and detecting potentially vulnerable subpopulations. As can be seen in Figure 2, the proportion of women reporting to have suffered physical or sexual violence is not uniform across the Spanish provinces, ranging from 7% to 45%. Also shocking is the result that, among these women, only a small fraction of them have searched for health services (excluding hospitalization), and that there is a negative correlation between the proportion of gender-based violence victims and usage of health services (correlation of -0.26, 90% CI: -0.47 to -0.04), probably related to factors like rurality, ease of access to health services and different age structures among provinces, which will also be accounted for in the framework of this project.

Figure 2. Estimated proportion (in percentage) of gender-based violence (physical and/or sexual) in each Spanish province (left-hand map) and estimated proportion (in percentage) of usage of health services excluding hospitalization among gender-based violence victims (right-hand map). Source: Self- generated based on data from the population-level survey on gender-based violence in Spain.

Figure 2. Estimated proportion (in percentage) of gender-based violence (physical and/or sexual) in each Spanish province (left-hand map) and estimated proportion (in percentage) of usage of health services excluding hospitalization among gender-based violence victims (right-hand map). Source: Self- generated based on data from the population-level survey on gender-based violence in Spain.

Aims and hypotheses

This project’s overarching objective is to improve the social and health care model for the victim and her environment in cases of gender-based violence, using advanced data science and mathematical modeling methods. We have set four specific objectives, which are further described below:

O1. Estimate the actual evolution of the number of gender-based violence cases, also covering the unreported cases, using the time series of registered cases by basic health area corresponding to the Northern Metropolitan Health Region.

O2. Quantify the impact in reducing the underreporting issue of the new protocol to prevent gender-based violence introduced in the primary care system in the Northern Metropolitan Health Region in Catalonia in June 2018 and the training intervention conducted to sensibilize involved health professionals.

O3. Predict when women may be victims of gender-based violence early on by developing new ensemble models based on a broad collection of clinical and sociodemographic features and identify which of these features are best predictors of such violence to create new knowledge in the field.

O4. Develop technology capable of predicting women’s characteristics compatible with a scenario of gender-based violence to assist health and social care professionals in identifying potential scenarios of this sort of violence in a clear and transparent manner.

Innovation

The current project is novel at least in two ways: First, it uses real-world data that have not been analyzed in much detail before to estimate underreporting, predict potential victims of gender-based violence as well as generate accurate knowledge in the field to allow professionals updating their protocols and perspectives on certain aspects of the problem. Second, we will develop more flexible and appropriate methods for underreporting estimation and predictive purposes (see specific objectives described above), with the aim of improving the existing counterparts’ performances, thus providing more accurate outcomes and outputs from this project. In terms of data, for underreporting estimation (specific objectives O1. and O2., see above), we will use all the primary care diagnoses related to gender-based violence reported in the Northern Metropolitan Health Region in Catalonia (Spain) between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2021. To date, underreporting in such data has not been studied or accurately estimated, even though professionals in the field are aware that this is a common phenomenon of gender-based violence data which worsen inferences and related conclusions. In addition, for the predictive purposes outlined in the third and fourth specific objectives (see specific objectives O3. and O4. above), we will use data from the macro-survey on violence against women, which was performed on a representative sample of 9.568 women aged over 16. The survey covered aspects related to sexual, psychological, and economic violence from a current or former partners, physical and sexual violence from non-partners, sexual harassment, and stalking (all these manifestations of violence englobed in the concept of gender-based violence), as well as other demographical and societal data such as age, education level, country of birth, marital status at the time of the survey, employment detail at the time of the survey, number of sons, partner’s gender, partner’s education level and partner’s nationality, among others. For knowledge generation in the field (stated in the specific objective O3.), we will use data from the macro-survey described above, e.g., detecting the variables that best predicted risk of suffering gender-based violence, as well as new data consisting of women’s characteristics such as age and nationality, and women’s health indicators such as the number of medical visits, number and status of pregnancies, number of miscarriages, urgency contraception usage, tobacco and alcohol status, physical activity, sexual relations, STI risk status, number of cytologies. These characteristics will be available for a sample of women who have already been diagnosed as victims of gender-based violence, as well as for a sample of women from the same region who have used the public health system at least once during the same time period although they were not diagnosed as victims of gender-based violence. We will use two different sets of data to create knowledge in the form of features or attributes that best characterize victims of gender-based violence given that the macro- survey does not contain information related to women’s health status, and this may be also relevant for the quick identification of potential victims, especially for the health professionals. To our knowledge, none of these datasets have been used for predictive purposes or for field knowledge production (in the terms stated in this project, i.e., for the detection of features as good predictors of gender-based violence) so far, even though both contain a wealth of rich and accurate information. In terms of methods development, for the purpose of underreporting estimation, we will extend recently proposed models based on longitudinal data analysis to analyze whether the incidence of the reported cases of gender-based violence has been underreported, as well as to estimate the frequency and intensity of the underreporting issue (specific objectives O1. and O2.). This model will be extended in different ways: Firstly, we will consider a time-varying underreporting scenario, i.e., we will allow underreporting parameters (frequency and intensity) to vary over time by considering appropriate and flexible functions. Second, we will investigate more complex structures for the latent processes, e.g., allowing more complex auto-correlation structures that may be more realistic, as well as more flexible models for characterizing the underreporting phenomenon. In addition, we will explore new alternatives for developing models for underreporting identification and estimation following methods based on N-mixture models, Bayesian approaches or capture-recapture methods, among other approaches. Finally, for achieving the third and fourth specific objectives (O3. and O4.), we will develop: (i) methods for variable selection and dimensionality reduction and (ii) prediction methods based on ensemble approaches. For the first point before, given that a large number of important potential predictors for gender-based violence identification is available, we will investigate and develop new methods for variable selection based on knockoffs. Knockoff-based methods are a general framework for controlling the false discovery rate in variable selection procedures. The idea here is to investigate some of these existing techniques to select a collection of variables that are actually effective predictors of gender-based violence and extend some of the existing knockoff-based methods to improve the current project’s outcomes. Techniques for variable selection based on knockoffs are relatively new since they have not been explored in detail to date, and while there is a lot of good literature out there, there is still a lot of room for improvements in this area. For the second point, using the outcomes provided by the previous step (i), we will develop new prediction models based on ensemble techniques, which very often provide better predictive performances controlling overfitting, lessening the curse of dimensionality, mitigating class imbalances, etc. The idea behind ensemble techniques is to optimally combine a varied collection of weak learners that each captures specific aspects of the data, and a key point is thus the way we combine such weak learners. This project will build on different ensemble approaches, including adaptive boosting (AdaBoost), gradient boosting machines, stacked generalization techniques, and ensemble deep learning. We will extend some of these ensemble methods to provide a powerful predictive machine able to predict women at risk of suffering gender-based violence, guaranteeing both low false-positive and false- negative rates. To date, these approaches have never been used before to prevent gender-based violence in the terms proposed by this project.

All data handling and statistical analyses will be conducted by developing new programs based on R language (version 4.1.0), and all codes and algorithms generated by this project will be available from public repositories as GitHub or CRAN for full transparency.

Further details related to methods development will be described below in Section Methodology.

Expected outcomes and outputs

A number of outcomes and outputs will be generated within the framework of this research project, in terms of methods development and related technologies, as well as knowledge generation in the field. In the first place, in terms of methods development and related technologies for underreporting estimation (specific objectives O1. and O2.), new approaches to the analysis of this phenomenon in data will be developed and integrated in the form of an R package, freely available and auditable to the entire data science community. These extended methods will particularly be used to estimate the true burden of gender-based violence in Catalonia in the period 2010-2021 and will allow us to estimate the magnitude of the unseen part of the problem, likely comparable to that of other neighboring countries. All these results and resources will be included in a web-page repository, available to the scientific community as well as the general public, allowing everyone to have a better understanding of the real extent of the problem. Second, in terms of methods development and related technologies for prediction methods construction (specific objectives O3. and O4.), we will provide a prediction technology aimed at estimating the risk of a certain woman suffering gender-based violence based on her social and clinical characteristics, so that it will be used as a potentially helpful and transparent guide for the professionals in the field. This technology will be adapted and incorporated in the software used by public health system professionals for new diagnoses reporting (e-CAP environment). In addition to the technologies described above for underreporting estimation and prediction purposes, we plan to publish our developed methods and related technologies in top-tier research journals in statistics and probability. We plan particularly to produce two papers with a methodological scope, one with the proposed model for underreporting estimation and another with the proposed predictive learning model. We also plan to present our methods in national and international conferences such as International Workshop on Statistical Modelling (IWSM), national and international conferences of respectively the Spanish Biometric Society and the International Biometric Society, among others. Secondly, in terms of knowledge generation in the field, the estimation of underreporting of the number of gender-based violence victims in the Northern Metropolitan Health Region of Catalonia (Spain) between 2010 and 2021 will provide knowledge not only about the estimated frequency and intensity of such a phenomenon in each basic health area, but also about the estimated underreporting parameters’ evolution over time, which can be used to determine if, e.g., the training interventions undertaken with health professionals in a studied basic health area had a significant influence on the evolution of gender-based violence underreporting. With robust estimates of the underreporting parameters (i.e., frequency and intensity) given by our developed models and implemented in the above-described technologies, we will be able to help the community understand the scope of the phenomenon in recent years and its evolution until now. In addition, knowledge of the magnitude of the phenomenon will assist professionals in developing more appropriate health policies and measures to control and (ideally) reduce the impact of underreporting in gender-based violence-related data. Finally, this information will also be helpful to adjust inferences and related conclusions based on data on gender-based violence. On the other hand, the knowledge provided by the prediction learning technology, e.g., identification of clinical and sociodemographic characteristics that are particularly good indicators of gender-based violence victims, can be used to better understand the problem, as well as formulate new practices for health professionals and train them more accurately based on data-based results. In addition to the new knowledge that this research project will bring to the field, we plan to produce two papers for top applied scientific journals. Although the described outcomes and results that this data science and statistical modeling approach can produce in order to better understand the real burden of gender-based violence and identifying the characteristics of potential victims overcoming possible human biases and prejudices, to the date this path has been little explored, while this project aims to achieve not only local answers to socially relevant research questions but also to provide methodological and technological tools that could be adapted and used in different contexts.

Social relevance

According to the United Nations organization (UN), gender-based violence refers to harmful acts directed at an individual based on their gender. It is rooted in gender inequality, the abuse of power and harmful norms. Gender-based violence is a serious violation of human rights and a life-threatening health and protection issue. It is estimated that one in three women will experience sexual or physical violence in their lifetime worldwide, especially in situations of potential vulnerability as forced displacements, wars, or economic crisis. Despite theoretical and regulatory advances in the field of recognition of women’s rights, the formal elimination of references to women’s honor and honesty, and the replacement of these references by sexual freedom, many patriarchal structures in the legal and social understanding of sexual violence remain in the text of our laws, especially in their interpretation. The large population-level survey conducted in Spain in 2019 including 9,568 interviewed women with 16 years or more revealed that gender-based violence is still an important public health issue, as it shows, among other relevant results, that more than 50% of Spanish women older than 16 years have suffered gender-based violence at some point in their lives. Also concerning is that the proportion of victims of gender-based violence is larger among younger women. This study also reveals that only a small fraction of victims seeks professional help after suffering an episode of gender-based violence. For instance, only the 6.5% of victims of sexual violence received medical assistance after the aggression, making it very complicated for public health system professionals to diagnose these cases and leading to severely underestimated records. In addition, unlike other forms of sexist violence, sexual violence still involves a very strong social stigma, and its understanding is often full of stereotypes and prejudices that severely affect victims. These phenomena, of course, are not exclusive to Catalonia or Spain, as they are widely documented around the world and are also the starting point for this diagnosis. Therefore, the results and methodological advances obtained using these data will be directly applicable worldwide, even in very different realities and will certainly make a difference in our understanding and fight against gender- based violence in all its forms.

Methodology

Let’s assume that the actual weekly number of GBV cases $X_t$ follows a Poisson distribution with mean $\lambda$, which is increased in a factor $\beta$ in the mandatory confinement period (2020 March 14th to 2020 June 24th), i.e., $E(X_t) = \lambda+I(t) \cdot \beta$ where $I(t)$ takes the value 1 if $t$ falls within the mandatory confinement period and 0 otherwise.

The number of cases diagnosed within the public primary care system, $Y_t$, is just a part of the actual process, expressed as

Y_t = \begin{cases}

q_0 \circ X_t, t \leq t' \\

q_t \circ X_t, t > t'

\end{cases}

where $\circ$ is the binomial thinning operator, defined as \(q_t \circ X_t = \sum_{i=1}^{X_t} Z_i\), with $Z_i$ independent and identically distributed Bernoulli random variables with probability of success $q_t$ and $q_t = q_0 + \frac{t-t’}{\alpha-t’} \cdot (1-q_0)$ for $t > t’$, where $t’$ is the changing point at which the sensibilization training for primary care professionals starts impacting the weekly number of diagnoses. Additionally, an alternative modelling of $q_t$ as $q_t = 1- (1-q_0)e^{(-\alpha \cdot (t-t’))}$ was considered and compared to the previous one in terms of Deviance Information Criterion (DIC). Each subarea was modelled according to its best fitting approach.

It should also be noted that $\alpha$ is the moment when $q_{\alpha}=1$, i.e., the registered and observed processes coincide. It is important to note that the number of GBV cases $X_t$ is not directly observed, and only the number of diagnosed cases $Y_t$ is observed. The previous model assumes that $Y_t$ only reports a fraction $q_t$ of the total number of GBV cases. All the parameters ($q_0$, $\lambda$, $\beta$, $\alpha$ and $t’$) are estimated by Gibbs sampling using the R2jags package (Yu-Sung and Masanao, 2021), using appropriate priors based on the available information. In order to avoid non-identifyability of the model defined by Equation (1), the actual average number of GBV cases in each subarea on the non-Covid period (parameter $\lambda$) has a normal prior distribution with mean based on several realistic scenarios:

- Scenario 1: The expected situation according to the results of the macro survey conducted by the Spanish Ministry of Equality, i.e., around 32% of women in the Barcelona area have suffered physical or sexual GBV at some point in their lives, and only around 16% of the victims sought medical care after suffering such an episode (excluding hospital admissions). It should be stressed that this is the most conservative scenario, as it assumes that the results of the survey are not underestimating the prevalence of GBV cases and subsequent usage of health services, which is dubious to say the least.

- Scenario 2: Assuming again that around 32% of women in the Barcelona area have suffered physical or sexual GBV at some point in their lives, but considering that 50% of the victims seek medical care after suffering such an episode (excluding hospital admissions).

- Scenario 3: Assuming again that around 32% of women in the Barcelona area have suffered physical or sexual GBV at some point in their lives, but considering that 90% of the victims seek medical care after suffering such an episode (excluding hospital admissions). This scenario is especially interesting from a preventive perspective, as it is known that 90% of the population attends a primary health center at least once every two years and, therefore, this is scenario considers primary care as the reference system for cases of GBV.

Once the parameters have been estimated, the most likely process can be reconstructed taking into account that $Y_i \mid X_i \sim Binom(x_i, q_t)$. At each time $t$ with $j$ reported cases, the most likely number of gender-based violence cases is the value $\nu$ that maximizes the probability

\begin{aligned}

f(\nu) &= P(X=\nu \mid Y=j) \propto P(Y=j \mid X=\nu) \cdot P(X=\nu) = \\

&= \begin{cases}

0, j > \nu \\

\binom{\nu}{j} \cdot q_t^j \cdot (1-q_t)^{\nu-j} \cdot \frac{e^{- (\lambda + I(t) \cdot \beta)} \cdot (\lambda + I(t) \cdot \beta)^{\nu}}{\nu !}, j \leq \nu

\end{cases}

\end{aligned}

A thorough simulation study reproducing the described structure with different parameter values has been conducted in order to assess whether the original values can be recovered by using this estimation method and to assess the model performance.

Results

The main preliminary results of the project can be consulted here. Some relevant descriptions can be found here.

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by the Social Observatory of the “la Caixa” Foundation as part of the project LCF/PR/SR22/52570005.